People at a job fair in Miami, Fla. on May 2, 2013.

The 2008 financial crisis has left us with no shortage of economic problems, but among the most worrisome is the scourge of long-term unemployment. Though the official unemployment rate has fallen from more than 10% in October 2009 to 7.4% today, the labor market remains a brutal place for the 4.2 million long-term unemployed, whom the Labor Department defines as workers who have been out of work for six months or more.

This trait distinguishes the 2008–09 recession from past downturns. At the depth of the recession we experienced in the early 1980s, for example, just 25% of the unemployed were without jobs for more than six months. Four years into our current recovery, that number remains close to 40%.

(MORE: Falcone Down: Hedge-Fund Titan Settles With SEC, Faces Wall Street Ban)

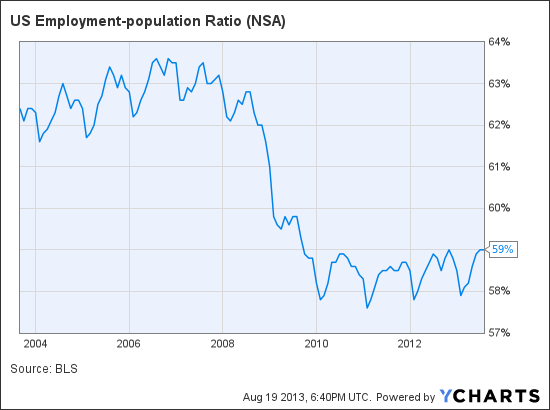

So what accounts for this? The Urban Institute is publishing a series of papers today on the issue overseen by economist Gregory Acs. Acs says the No. 1 culprit has been the overall limpness of the economic recovery. Even though we have seen a significant decline in the unemployment rate, overall economic and job growth has been muted. One statistic that illustrates this is the percentage of the total population that is employed, which has remained depressed despite the uptick in the unemployment rate:

The reasons for this are twofold. One is that worker productivity has been growing more slowly than in the past (meaning the amount of work per worker isn’t rising as fast). The other is that many “discouraged” workers are dropping out of, or never joining, the workforce — so they aren’t counted among the unemployed.

In other words, Acs says, the decline in the unemployment rate has overstated the strength of the recovery — and the economy has simply not grown fast enough to convince enough employers to hire someone who hasn’t held a job in six months or more.

Why this is truer than in the past — why, that is, employers have been less inclined to hire the long-term unemployed than other unemployed workers — remains somewhat unclear. But it is a fact: Wharton management professor Peter Cappelli has written about research showing that job applicants who have been unemployed for a month or more are much less likely to get a response from employers. It would appear that employers are simply using the length employees are out of work as a mental shortcut for how valuable they would be.

In fact, there isn’t any reason to believe workers who have been out of work for six months, or even longer, are less valuable than the continuously employed. Writes Cappelli:

The way to get hiring of the long-term unemployed started is to recognize that there is no objective case in this economy for not considering a candidate who has been out of work for a while. Therefore, excluding them out of hand is a form of prejudice. The people at the top of organizations need to point out that excluding such candidates is likely costing us money because we are ignoring potential good hires, just as it costs us money to exclude women, minorities, older individuals and anyone else who has the potential to do the job.

Who are the long-term unemployed? The Urban Institute’s research shows that the common presumption that the long-term unemployed are mainly older workers from specific industries like manufacturing doesn’t reflect reality. In fact, the long-term unemployed are fairly evenly distributed across the age and industry spectrum, with the notable exception being the construction industry. (Construction workers are both much more likely to be long-term unemployed and newly employed, which indicates both the severity of the housing slump, and the extent to which the nascent real estate recovery is generating jobs.)

In short, the long-term-unemployment problem appears to be an extension of the larger employment crisis in America, and one that’s been masked by a falling unemployment rate. The long-term unemployed are simply those workers who are a little less lucky, or a little less valuable to employers than the rest of the unemployed workforce. And the solution to the employment crisis is only going to be solved by faster growth. As Acs tells me, “We wouldn’t be having this conversation if the economy were growing at 4%.”

It’s a shame that a paralyzed Congress can’t seem to agree on any policies that might help our convalescent job market. But it would also appear that the private sector is helping to compound the bad luck of the long-term unemployed by not considering them for the jobs that are open.