Why treadmills? That was my first question to Damian Kulash, the frontman of indie rock band OK Go. You probably remember the quirky video of Kulash and his bandmates dancing on gym equipment, which debuted on a recently launched video-sharing website called YouTube back in 2006. The group had already gotten a taste of viral success with a goofy dance video shot in Kulash’s back yard that was downloaded 300,000 times. They knew an even more outlandish video was the most direct and affordable way to widen their audience.

“It was the band, my sister, eight treadmills in a room, and we just spent 10 days figuring out what we were going to do with it all,” he says.

(MORE: Revenue Up, Piracy Down: Has the Music Industry Finally Turned a Corner?)

The final product, the music video for “Here It Goes Again,” racked up 800,000 views on YouTube in 24 hours and more than 20 million within a year. If that seems like a small number now, that’s a testament to how the video format has exploded in popularity online in the past seven years. When OK Go first went viral, the music video seemed rudderless, an expensive relic of the industry’s pre-Napster boom times. Now a single music video (you can guess the one) has been viewed more than a billion times on YouTube alone. Thanks to technological innovation, creativity and business savvy, the music video has become the most popular visual genre of the Web.

Rise, Fall and Resurrection

Since the period when The Beatles developed feature film musicals tied to their early albums Help! and A Hard Day’s Night, music fans have craved visuals to go along with their tunes. MTV fed that desire 24 hours a day when it launched in 1981, offering artists a visual platform to promote their music. Some of pop culture’s most iconic moments—Michael Jackson thrilling a horde of zombies, Nirvana moshing in a murky gymnasium, Britney Spears gyrating in a Catholic schoolgirl outfit—come from a time when videos were synonymous with television. They were so popular that MTV created a daily celebration of them, called Total Request Live. It became a cultural touchstone for Millennials and attracted almost 800,000 daily viewers at its peak in 1999, according to Nielsen.

(LIST: The 30 All-TIME Best Music Videos)

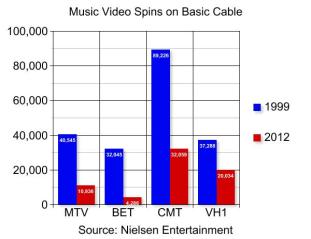

But when the industry’s fortunes turned at the start of the millennium, so did the video’s. Budgets shrunk. TRL’s ratings tanked, and the program was cancelled in 2008. Popular reality shows ate into more and more of the time that had been reserved for actual music television. In 1999, the four basic cable music channels—MTV, VH1, BET and CMT—played about 200,000 music videos between them, according to Nielsen Entertainment. By 2012 the number had fallen to less than 70,000. “Many people left them for dead,” says Jonathan Wells, one of the curators of Spectacle: The Music Video, an exhibition opening Wednesday at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image.

Even as videos were falling off the cable map, they were persistently growing in importance online, especially on YouTube. The site’s most popular videos used to be quirky homemade efforts like “The Evolution of Dance” and “Charlie Bit My Finger.” Now, of the site’s top 30 most-viewed clips of all time, all but one are music videos.

The YouTube resurgence accelerated once record labels finally discovered how to profit from videos online. In 2009 Universal Music Group and Sony Music Entertainment launched Vevo, a music video website that licenses official versions of artists’ videos across the Web and sells ads against them. “Before Vevo, music videos were online, but there wasn’t any money being made,” says company CEO Rio Caraeff. “They were available, but there was no business.” Vevo now dominates the YouTube charts and pulled in 41 billion worldwide views across all platforms in 2012 from a catalogue of about 75,000 videos. The average CPM rate (cost per thousand views) for a music video online has increased tenfold since Vevo launched, Caraeff says, from $3 to more than $30. Mega-viral videos like “Gangnam Style” have generated hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue for artists and labels.

“We’re actually producing more videos these days,” says industry veteran Danny Lockwood, Senior Vice President, Creative and Video Production at Capitol Music Group. “The viewing of videos online has really shifted the financial paradigm.”

It’s not just the official, label-approved creations that comprise the music video market today, though. Fan-made spoofs, parodies and covers are just as easy to find as the original on YouTube and are sometimes even more popular. Baauer’s “Harlem Shake” doesn’t even have an official video, but the song ignited a viral video craze this winter that led to the creation of more than 500,000 videos that have gained more than a billion views since February 1. Thanks to YouTube’s Content ID system, Baauer and his label profited from those videos by claiming their ownership of the song.

A More Prominent Role, But Fewer Resources

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8UVNT4wvIGY]

For artists, there’s a growing awareness that videos can have just as much value as the songs themselves, especially in a media environment where both can be streamed instead of purchased anyway. “We don’t view them as promotional materials for the ‘real’ thing, the song,” Kulash says. “To us the song is the real thing when you’re listening to the song and the music video is the real thing when you’re watching the music video.”

After treadmills brought them fame, OK Go decided to double down on the bet that entertaining videos would help them secure both fans and money. They’ve since made videos where they built an elaborate Rube Goldberg machine, danced with dogs and turned a car into a musical instrument. The band left their label, EMI, back in 2010 partly because they thought they could monetize their new media ventures better on their own. Now their videos are so famous that they’re able to attract corporate sponsors like State Farm to pay for them.

(MORE: How Sesame Street Counted All the Way to 1 Billion YouTube Views)

Even as views and revenues have increased, though, budgets have mostly remained stubbornly low. “In the mid-90s, it was perfectly reasonable to spend half a million dollars on a music video,” says James Frost, a filmmaker who’s directed more than 60 music videos for artists such as Coldplay and OK Go. “[Now] I rarely see a budget that comes in over $15,000 to $20,000. And that’s for established artists.”

Frost says directors have had to broaden their skillset, learning how to work with smaller crews and edit their own film. Technology has helped in the transition—no one had Final Cut Pro to use in the MTV heyday, or a billion-user website where they could post their work for free. But for directors and production staff, videos today are more a labor of love than a viable alternative to shooting commercials. “Now, when [crews] do a music video, they’re doing it because they’re either good friends with the director or they’re doing it because they love the band,” Frost says. “The spirit of the whole job has changed.”

Falling budgets have also brought a heightened amount of experimentation as music video production becomes more affordable. The visually striking video for Gotye’s “Somebody That I Used to Know” had a budget of less than $30,000. Now it’s one of the most popular videos in YouTube history with more than 380 million views. “I actually was worried when I first made it that maybe it was a little bit alienating,” director Natasha Pincus says of the video, which features Gotye in the nude. “I was hoping it would still reach his core audience. I had no expectation it would also reach this whole new audience…YouTube’s democratized video art for the masses.”

A Multifaceted Future

How does the music video evolve from here? Like all other media, it’s going quickly to smartphones—a quarter of Vevo’s 4 billion monthly streams now come from mobile devices, and artists like Bjork have experimented with releasing their songs and videos via apps. It’s also going interactive. Bands like Arcade Fire, Cold War Kids and the Red Hot Chilli Peppers have created interactive music videos that utilize digital tools like webcams and Google Maps.

In the interactive film for Arcade Fire’s song “Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains),” viewers dance in front of a webcam to control the tempo of the video.

“It offers a different way to connect to the people,” says Vincent Morisset, the director of Arcade Fire’s interactive videos for “Neon Bible” and “Sprawl II.” “It can be participatory. People can get involved in the creation.”

Videos are even going old-school. Vevo, the website that standardized music videos on-demand, also believes people want MTV-esque, scheduled programming at times. Earlier this month the company launched a new streaming channel, Vevo TV, that plays hand-picked music videos and music-oriented original shows 24 hours a day. Vevo hopes to roll the channel out on cable by the end of the year.

(MORE: Behind the Hit ‘Bible’ Miniseries: The Man Who Helps Hollywood Get Religion)

Music videos have taken over YouTube, they may soon invade Spotify, and they’ll be expanding in your cable lineup sometime soon (worth noting that Viacom runs several all-music MTV and VH1 video channels available on extended cable). They’re blurring old lines that used to separate art from promotion. They’re so relevant to how we consume music and define what’s popular that Billboard recently added YouTube views to its formula for charting the weekly Hot 100.

OK Go’s Kulash predicts a world where recorded music is not the central element of a musical artist’s identity. Instead it will be part of a digital repertoire that might include songs, videos, apps and games—his band, at least, has already embraced such a future. “Our value comes from wherever we can find it,” he says. “If the public chooses our stuff, that gives us a lot of power. The metric doesn’t really matter to us and the platform doesn’t really matter to us. If people are excited about what we’re doing, it’s very easy for us to go to corporate sponsors or even the old traditional music industry and get them to support what we’re doing.”

Why treadmills? That was my first question to Damian Kulash, the frontman of indie rock band OK Go. You probably remember the quirky video of Kulash and his bandmates dancing on gym equipment, which debuted on a recently launched video-sharing website called YouTube back in 2006. The group had already gotten a taste of viral success with a goofy dance video shot in Kulash’s back yard that was downloaded 300,000 times. They knew an even more outlandish video was the most direct and affordable way to widen their audience.

“It was the band, my sister, eight treadmills in a room, and we just spent 10 days figuring out what we were going to do with it all,” he says.

(MORE: Revenue Up, Piracy Down: Has the Music Industry Finally Turned a Corner?)

The final product, the music video for “Here It Goes Again,” racked up 800,000 views on YouTube in 24 hours and more than 20 million within a year. If that seems like a small number now, that’s a testament to how the video format has exploded in popularity online in the past seven years. When OK Go first went viral, the music video seemed rudderless, an expensive relic of the industry’s pre-Napster boom times. Now a single music video (you can guess the one) has been viewed more than a billion times on YouTube alone. Thanks to technological innovation, creativity and business savvy, the music video has become the most popular visual genre of the Web.

Rise, Fall and Resurrection

Since the period when The Beatles developed feature film musicals tied to their early albums Help! and A Hard Day’s Night, music fans have craved visuals to go along with their tunes. MTV fed that desire 24 hours a day when it launched in 1981, offering artists a visual platform to promote their music. Some of pop culture’s most iconic moments—Michael Jackson thrilling a horde of zombies, Nirvana moshing in a murky gymnasium, Britney Spears gyrating in a Catholic schoolgirl outfit—come from a time when videos were synonymous with television. They were so popular that MTV created a daily celebration of them, called Total Request Live. It became a cultural touchstone for Millennials and attracted almost 800,000 daily viewers at its peak in 1999, according to Nielsen.

(LIST: The 30 All-TIME Best Music Videos)

But when the industry’s fortunes turned at the start of the millennium, so did the video’s. Budgets shrunk. TRL’s ratings tanked, and the program was cancelled in 2008. Popular reality shows ate into more and more of the time that had been reserved for actual music television. In 1999, the four basic cable music channels—MTV, VH1, BET and CMT—played about 200,000 music videos between them, according to Nielsen Entertainment. By 2012 the number had fallen to less than 70,000. “Many people left them for dead,” says Jonathan Wells, one of the curators of Spectacle: The Music Video, an exhibition opening Wednesday at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image.

Even as videos were falling off the cable map, they were persistently growing in importance online, especially on YouTube. The site’s most popular videos used to be quirky homemade efforts like “The Evolution of Dance” and “Charlie Bit My Finger.” Now, of the site’s top 30 most-viewed clips of all time, all but one are music videos.

The YouTube resurgence accelerated once record labels finally discovered how to profit from videos online. In 2009 Universal Music Group and Sony Music Entertainment launched Vevo, a music video website that licenses official versions of artists’ videos across the Web and sells ads against them. “Before Vevo, music videos were online, but there wasn’t any money being made,” says company CEO Rio Caraeff. “They were available, but there was no business.” Vevo now dominates the YouTube charts and pulled in 41 billion worldwide views across all platforms in 2012 from a catalogue of about 75,000 videos. The average CPM rate (cost per thousand views) for a music video online has increased tenfold since Vevo launched, Caraeff says, from $3 to more than $30. Mega-viral videos like “Gangnam Style” have generated hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue for artists and labels.

“We’re actually producing more videos these days,” says industry veteran Danny Lockwood, Senior Vice President, Creative and Video Production at Capitol Music Group. “The viewing of videos online has really shifted the financial paradigm.”

It’s not just the official, label-approved creations that comprise the music video market today, though. Fan-made spoofs, parodies and covers are just as easy to find as the original on YouTube and are sometimes even more popular. Baauer’s “Harlem Shake” doesn’t even have an official video, but the song ignited a viral video craze this winter that led to the creation of more than 500,000 videos that have gained more than a billion views since February 1. Thanks to YouTube’s Content ID system, Baauer and his label profited from those videos by claiming their ownership of the song.

A More Prominent Role, But Fewer Resources

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8UVNT4wvIGY]

For artists, there’s a growing awareness that videos can have just as much value as the songs themselves, especially in a media environment where both can be streamed instead of purchased anyway. “We don’t view them as promotional materials for the ‘real’ thing, the song,” Kulash says. “To us the song is the real thing when you’re listening to the song and the music video is the real thing when you’re watching the music video.”

After treadmills brought them fame, OK Go decided to double down on the bet that entertaining videos would help them secure both fans and money. They’ve since made videos where they built an elaborate Rube Goldberg machine, danced with dogs and turned a car into a musical instrument. The band left their label, EMI, back in 2010 partly because they thought they could monetize their new media ventures better on their own. Now their videos are so famous that they’re able to attract corporate sponsors like State Farm to pay for them.

(MORE: How Sesame Street Counted All the Way to 1 Billion YouTube Views)

Even as views and revenues have increased, though, budgets have mostly remained stubbornly low. “In the mid-90s, it was perfectly reasonable to spend half a million dollars on a music video,” says James Frost, a filmmaker who’s directed more than 60 music videos for artists such as Coldplay and OK Go. “[Now] I rarely see a budget that comes in over $15,000 to $20,000. And that’s for established artists.”

Frost says directors have had to broaden their skillset, learning how to work with smaller crews and edit their own film. Technology has helped in the transition—no one had Final Cut Pro to use in the MTV heyday, or a billion-user website where they could post their work for free. But for directors and production staff, videos today are more a labor of love than a viable alternative to shooting commercials. “Now, when [crews] do a music video, they’re doing it because they’re either good friends with the director or they’re doing it because they love the band,” Frost says. “The spirit of the whole job has changed.”

Falling budgets have also brought a heightened amount of experimentation as music video production becomes more affordable. The visually striking video for Gotye’s “Somebody That I Used to Know” had a budget of less than $30,000. Now it’s one of the most popular videos in YouTube history with more than 380 million views. “I actually was worried when I first made it that maybe it was a little bit alienating,” director Natasha Pincus says of the video, which features Gotye in the nude. “I was hoping it would still reach his core audience. I had no expectation it would also reach this whole new audience…YouTube’s democratized video art for the masses.”

A Multifaceted Future

How does the music video evolve from here? Like all other media, it’s going quickly to smartphones—a quarter of Vevo’s 4 billion monthly streams now come from mobile devices, and artists like Bjork have experimented with releasing their songs and videos via apps. It’s also going interactive. Bands like Arcade Fire, Cold War Kids and the Red Hot Chilli Peppers have created interactive music videos that utilize digital tools like webcams and Google Maps.

In the interactive film for Arcade Fire’s song “Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains),” viewers dance in front of a webcam to control the tempo of the video.

“It offers a different way to connect to the people,” says Vincent Morisset, the director of Arcade Fire’s interactive videos for “Neon Bible” and “Sprawl II.” “It can be participatory. People can get involved in the creation.”

Videos are even going old-school. Vevo, the website that standardized music videos on-demand, also believes people want MTV-esque, scheduled programming at times. Earlier this month the company launched a new streaming channel, Vevo TV, that plays hand-picked music videos and music-oriented original shows 24 hours a day. Vevo hopes to roll the channel out on cable by the end of the year.

(MORE: Behind the Hit ‘Bible’ Miniseries: The Man Who Helps Hollywood Get Religion)

Music videos have taken over YouTube, they may soon invade Spotify, and they’ll be expanding in your cable lineup sometime soon (worth noting that Viacom runs several all-music MTV and VH1 video channels available on extended cable). They’re blurring old lines that used to separate art from promotion. They’re so relevant to how we consume music and define what’s popular that Billboard recently added YouTube views to its formula for charting the weekly Hot 100.

OK Go’s Kulash predicts a world where recorded music is not the central element of a musical artist’s identity. Instead it will be part of a digital repertoire that might include songs, videos, apps and games—his band, at least, has already embraced such a future. “Our value comes from wherever we can find it,” he says. “If the public chooses our stuff, that gives us a lot of power. The metric doesn’t really matter to us and the platform doesn’t really matter to us. If people are excited about what we’re doing, it’s very easy for us to go to corporate sponsors or even the old traditional music industry and get them to support what we’re doing.”