On the outskirts of Nairobi, there’s a bright red cell-phone tower that delivers coverage to thousands of the city’s 3 million people. Inside the tower sit batteries with a high-tech design and a simple purpose: to provide backup power to keep calls connected even when the electrical grid goes down. The surprising thing is where these batteries are made. Not China, Japan or one of the other big Asian manufacturing powers. Instead they come from a plant in Schenectady, N.Y., a Rust Belt city once seen as a relic of an earlier industrial age. Now a General Electric factory on the site of a former turbine plant is churning out the batteries 24 hours a day. “People can’t get enough,” says Randy Rausch, a manager at the plant. “We’re shipping all over the world.”

The U.S. economy continues to struggle, and the weak March jobs report–just 88,000 positions were added–spooked the market. But step back and you’ll see a bright spot, perhaps the best economic news the U.S. has witnessed since the rise of Silicon Valley: made in the usa is making a comeback. Climbing out of the recession, the U.S. has seen its manufacturing growth outpace that of other advanced nations, with some 500,000 jobs created in the past three years. It marks the first time in more than a decade that the number of factory jobs has gone up instead of down. From ExOne’s 3-D-printing plant near Pittsburgh to Dow Chemical’s expanding ethylene and propylene production in Louisiana and Texas, which could create 35,000 jobs, American workers are busy making things that customers around the world want to buy–and defying the narrative of the nation’s supposedly inevitable manufacturing decline.

The past several months alone have seen some surprising reversals. Apple, famous for the city-size factories in China that produce its gadgets, decided to assemble one of its Mac computer lines in the U.S. Walmart, which pioneered global sourcing to find the lowest-priced goods for customers, said it would pump up spending with American suppliers by $50 billion over the next decade–and save money by doing so. Airbus will build JetBlue’s jets in Alabama. Meanwhile, in North Carolina’s furniture industry, which has lost 70,000 jobs to rivals abroad, Ashley Furniture is investing at least $80 million to build a new plant. “If you go back 10 years, we didn’t think we’d be manufacturing in the U.S.,” says Ashley’s CEO, Todd Wanek.

This isn’t a blip. It’s the sum of a powerful equation refiguring the global economy. U.S. factories increasingly have access to cheap energy, thanks to oil and gas from the shale boom. For companies outside the U.S., it’s the opposite: high global oil prices translate into costlier fuel for ships and planes, which means some labor savings from low-cost plants in China evaporate when the goods are shipped thousands of miles. And about those low-cost plants: workers from China to India are demanding and getting bigger paychecks, while U.S. companies have won massive concessions from unions over the past decade. Suddenly the math on outsourcing doesn’t look quite as attractive. Paul Ashworth, the chief U.S. economist for the research firm Capital Economics, is willing to go a step further. “The offshoring boom,” he says, “does appear to have largely run its course.”

Today’s U.S. factories aren’t the noisy places where your grandfather knocked in four bolts a minute for eight hours a day. Dungarees and lunch pails are out; computer skills and specialized training are in, since the new made-in-America economics is centered largely on cutting-edge technologies. The trick for U.S. companies is to develop new manufacturing techniques ahead of global competitors and then use them to produce goods more efficiently on superautomated factory floors. These factories of the future have more machines and fewer workers–and those workers must be able to master the machines. Many new manufacturing jobs require at least a two-year tech degree to complement artisan skills such as welding and milling. The bar will only get higher. Some experts believe it won’t be too long before employers expect a four-year degree–a job qualification that will eventually be required in many other places around the world too.

Understanding this new look is critical if the U.S. wants to nurture manufacturing and grow jobs. There are implications for educators (who must ensure that future workers have the right skills) as well as policymakers (who may have to set new educational standards). “Manufacturing is coming back, but it’s evolving into a very different type of animal than the one most people recognize today,” says James Manyika, a director at McKinsey Global Institute who specializes in global high tech. “We’re going to see new jobs, but nowhere near the number some people expect, especially in the short term.”

If the U.S. can get this right, though, the payoff will be tremendous. Labor statistics actually shortchange the importance of manufacturing because they mainly count jobs inside factories, and related positions in, say, Ford’s marketing department or at small businesses doing industrial design or creating software for big exporters don’t get tallied. Yet those jobs wouldn’t exist but for the big factories. The official figure for U.S. manufacturing employment, 9%, belies the importance of the sector for the overall economy. Manufacturing represents a whopping 67% of private-sector R&D spending as well as 30% of the country’s productivity growth. Every $1 of manufacturing activity returns $1.48 to the economy. “The ability to make things is fundamental to the ability to innovate things over the long term,” says Willy Shih, a Harvard Business School professor and co-author of Producing Prosperity: Why America Needs a Manufacturing Renaissance. “When you give up making products, you lose a lot of the added value.” In other words, what you make makes you.

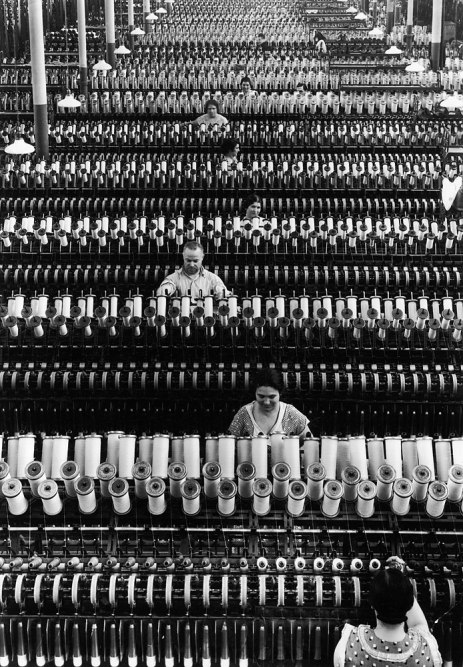

Photos From the Heyday of American Manufacturing

The Rise of the Industrial Internet

As soon as you step into ge’s battery plant–as clean and bright as a medical lab–you begin to see how it’s possible for a rich country like the U.S. to profitably export a commodity like batteries to Kenya and other emerging markets. The 200,000-sq.-ft. facility requires only 370 full-time employees, a mere 210 of them on the factory floor. The plant manager runs the operation–from lights to heat to inventory to purchasing and maintenance–from an iPad, on which he gets a real-time stream of data from wireless sensors embedded in each product rolling off the line.

The sensors let the batteries talk to GE via the Internet once they’ve left the factory. Each part of the product and, indeed, the factory, including the equipment and the workers who run it, will soon communicate with one another over the Internet. Not only does the data allow production to be monitored as it occurs; it can also help predict what might go wrong–recording, for instance, the average battery life in Bangladeshi heat vs. Mongolian cold. Designs will be altered in real time to reflect the knowledge. “It’s not about low-cost labor but about high technology,” says Prescott Logan, general manager of GE Energy Storage. The key to the division’s future, he says, is “listening to our batteries. We have to listen to what they are telling us and then think about how to monetize that.”

The approach has the potential to create entirely new businesses and jobs. While the technology in Schenectady has downsized the number of machinists needed to make a battery, it has also fueled the creation of a GE global research center in San Ramon, Calif. Over the past 20 months, 400 highly paid software engineers, data scientists and user-experience designers have been hired to churn out the software for the industrial Internet–otherwise known as the Internet of things–that will enable the equipment in the factories to talk. GE will add 200 more employees by the end of the year.

A Plant in Every Garage

A different glimpse into manufacturing’s future can be found near the roots of its past. Not far from Pittsburgh, whose vast furnaces turned out steel to build 20th century America, a new kind of industrial engine is powering up. Thanks in part to its proximity to the engineering powerhouse of Carnegie Mellon University, North Huntington, Pa., and towns like it are home to companies developing specialized metals, robotics and bioengineering–all critical to shoring up the nation’s ability to make things. But one technology being developed there may help foster a new wave of manufacturing outfits that will have as much in common with Silicon Valley start-ups as with the classic image of a factory.

The technology is called additive manufacturing, or more colloquially, 3-D printing. When most people talk about 3-D printing, they mean fun devices for hobbyists that can print plastic toys and other small objects when hooked up to a computer. When they talk about it at ExOne Corp., they’re describing something a lot bigger. Additive manufacturing involves what looks like spray-painting a metal object into existence. These 3-D printers lay down a very thin layer of stainless-steel powder or ceramic powder and fuse it with a liquid binder until a part–like a torque converter, heat exchanger or propeller blade–is built, layer by layer. ExOne’s employees are ramping up production lines to make 3-D printers at a price of about $400,000. Would-be manufacturing entrepreneurs can buy the devices and begin turning out high-tech metal parts for aerospace, automotive and other industries at lower cost and higher quality faster than offshore suppliers.

The 3-D-printing process is attractive because it can produce parts in shapes that would be impossible or unduly expensive through traditional manufacturing methods. That helps engineers rethink designs and outdo their competitors. S. Kent Rockwell, ExOne’s CEO, says one potential client asked him to reproduce a traditional heat exchanger and price it, which the firm did. The customer wasn’t that impressed. “Look,” Rockwell told him, “give me your optimal design for the heat exchanger.” The customer returned with a new design, doubtful that it could actually be manufactured. “We printed it in five days,” says Rockwell.

ExOne’s 3-D-printing machines, like a lot of new technology, will displace some labor. A foundry, for instance, no longer needs workers carting patterns around a warehouse; it can print molds and cores stored on a thumb drive, and no patterns are needed. An ExOne shop with 12 metal-printing machines needs only two employees per shift, supported by a design engineer–though they are higher-skilled workers. Rockwell envisions a thousand new industrial flowers blooming. “There’s a world of guys out there who say, If you can deliver parts in six or seven days, hey, I don’t need the machines. That’s where job creation is going to come from.” Overseas competitors will not be able to deliver that quickly or at the same level of quality.

Nurturing the Makers

The tale of additive printing is notable as much for its backstory as for its likely impact on the manufacturing economy. The technology, it turns out, was developed by MIT, nurtured by grants from the Office of Naval Research and the National Science Foundation before being adapted by private industry. It’s the kind of triple play–government, academia, industry–that’s held up as an ideal for public-private cooperation, as opposed to, say, the Solyndra debacle. Traditionally the U.S. hasn’t been as keen as other nations on those kinds of linkages. But now states are doing their own versions of an industrial policy. Virginia boasts the Commonwealth Center for Advanced Manufacturing to help companies translate research into high-tech products. To bridge the skills gap, North Carolina links community colleges with specific companies like Siemens.

President Obama has called for such efforts to go more national. He has proposed new manufacturing tax breaks, more robust R&D spending and vocational training for workers. Insiders say there are also conversations under way about how to create the kind of industrial policy–the phrase itself is still something of a political third rail–that would give U.S. manufacturing the kind of competitive advantages held for decades by the French and German economies, both of which enjoy trade surpluses when it comes to advanced manufacturing. Gene Sperling, director of the National Economic Council and a point person for Obama’s plans, is pushing a number of policies that sound more like Germany than the U.S., including the development of high-end-manufacturing research institutes to knit together private companies, educators and public resources. But Sperling says these policies are vital–and often misunderstood.

“Industrial policy suggests a top-down government effort to pick winners and losers, which is not good policy,” says Sperling. “What is sound policy is recognizing that location matters because manufacturing has innovation benefits that spill over to the economy at large, just like the location of R&D does. Policy that supports creating strong manufacturing ecosystems is not only economically sound; it is economically imperative.”

It also means creating federally funded research centers, including one to promote 3-D printing: the National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute in Youngstown, Ohio. The institute, which received a $30 million federal grant, will connect 32,000 manufacturers across the Rust Belt with top universities like Carnegie Mellon and technical experts from the Departments of Defense and Energy as well as NASA to accelerate innovation in key areas of high-tech manufacturing. It’s a system modeled on Germany’s Fraunhofer institutes, which have been widely credited with keeping wages and competitiveness high in that country even in the face of competition from countries like China. This year, the U.S. government will hold competitions and award similar grants for three more institutes nationwide. “We believe there can be a manufacturing renaissance in this country if we are smart about how to put some wind at the back of the trends moving in that direction,” Sperling says.

Competitive Edge

While new technologies like 3-d printing point to a brighter future for U.S. manufacturing, there are reasons for optimism in the present as well. The American worker is more competitive than you might think. For a long time, it seemed as if the cost gap with developing nations that swallowed millions of U.S. jobs would never close. But inevitably, it does. Emerging nations keep emerging: they get richer, wages rise, and factories abroad just don’t stay as cheap as they used to be. China is promising 13% average annual pay increases for minimum-wage workers as it moves toward a consumer society. And workers, in turn, are demanding more. Witness the groundbreaking union deal at China’s Foxconn electronics company, the outsourcer of choice for many American firms like Apple. Foxconn has been increasing pay over the past couple of years.

The comparison is even more favorable when you look at Europe, where manufacturing costs can be 15% to 25% higher than in the U.S. That is one reason firms such as Rolls-Royce and Volkswagen are expanding in America. To help fill its $96 billion worth of orders, Rolls recently announced a $136 million addition to its Advanced Airfoil Machining Facility south of Richmond, Va. In July, VW’s year-old assembly plant in Chattanooga, Tenn., added a third shift, boosting employment to 3,300 for a company that in the 1980s had stopped manufacturing in the U.S. “It’s about the inflexibility of the European workforce,” says Boston Consulting Group (BCG) senior partner Hal Sirkin. “No one admits it, but you are going to see more and more of it.” BCG estimates that there will be 6,840 new job openings in manufacturing in Virginia’s former tobacco region by 2017, creating a shortage of about 1,000 skilled workers.

Based solely on wages, of course, American workers aren’t a bargain compared with workers in emerging economies; they still make 7.4 times as much per hour as their Chinese counterparts. But increasingly, the cost arbitrage done by companies when deciding where to put jobs isn’t just about hourly pay. It’s also about relative labor productivity–which has been rising sharply in the U.S. over the past decade while remaining flat in China–as well as how flexible a workforce is, how close factories are to customers (which reduces the time needed to meet orders), what kind of subsidies states can offer companies for manufacturing and how well a company can leverage all that to cope with quickly changing customer demands. Add the effect of those higher oil prices worldwide–ratcheting up long-distance shipping costs–and there are sound economic arguments for buying American.

Bob Parsons, the head of Parsons Co., a midsize Illinois-based firm that does small runs of specialty parts for Caterpillar, says he’s increasingly getting business that might have gone to China or elsewhere. “We can do faster delivery with higher quality,” he says. “By the time you factor it all in, it makes sense to keep some of that work here. I think the insourcing trend is going to be huge.”

All these factors are reflected in Ashley Furniture’s decision to spend at least $80 million to build a new plant south of Winston-Salem, N.C., that will employ 500 people. It represents the reshoring of a traditional industry in a state that had lost jobs to China. According to Wanek, Ashley’s CEO, speed in meeting customer demands has never been more crucial. “Today the expectation is that you’d better be there in a week and it had better be perfect,” he says. The company still sources some items globally–glass and mirrors–but heavy components and upholstery are made in the U.S.

Workers are expected to step up their game. At Ashley, they are schooled in the continuous-improvement model used by Toyota–known as kaizen–which Ashley translates as “systems thinking” to improve quality and efficiency while reducing cost. It works as well for armoires as it does for autos. Wanek says Ashley will reward workers who are adaptive. Part of that involves acquiring new skills while on the job and taking responsibility for devising and implementing improvements. In exchange, workers can get profit sharing tied to company performance. “If we’re going to compete, we need people who are willing to step out of their comfort zone and embrace change,” Wanek says.

The takeaway is clear. China may still be the factory of the world, but the most advanced American exporters are taking manufacturing to an entirely new level. The gains won’t be distributed evenly in the U.S.–by geography or by industry. Despite Apple’s highly publicized announcement about manufacturing in the U.S., labor-intensive, highly tradable industries like consumer electronics are unlikely to return en masse. Energy- and resource-intensive industries (chemicals, wood products, heavy machinery and appliances) may do better, powered by that cheaper homegrown energy. It’s win-win when companies can combine low-cost energy with more productive local labor and cost-saving automation technology.

“We are probably the most competitive, on a global basis, that we’ve been in the past 30 years,” says GE CEO Jeff Immelt, who led Obama’s jobs council. “Will U.S. manufacturing go from 9% to 30% of all jobs? That’s unlikely. But could you see a steady increase in jobs over the next quarters and years? I think that will happen.” Indeed, it may be our best hope for real, shared economic recovery in the USA.

Correction Appended: April 12, 2013

The original version of this story misidentified the location of the National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute.